Experts Highlight Role of Digital Tools in Reducing COVID-19 Transmission

Like a wind-driven wildfire, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to flare and race across the U.S. and around the world, jumping firebreaks to threaten health and livelihoods and imperil long-term economic sustainability.

Short of a vaccine, digital contact tracing apps—coupled with a sustained commitment to social distancing and masks—offer the hope for arresting the virus’ spread, two health technology experts recently told Pacific Business Group on Health (PBGH) members.

Related digital tools known as health verification apps can help support and modulate community re-openings by aligning self-reported health assessments with organization-and site-specific guidelines, according to Brian McClendon and Marci Nielsen, Ph.D. co-founders of the CVKey Project. The two presented during a PBGH webinar June 26.

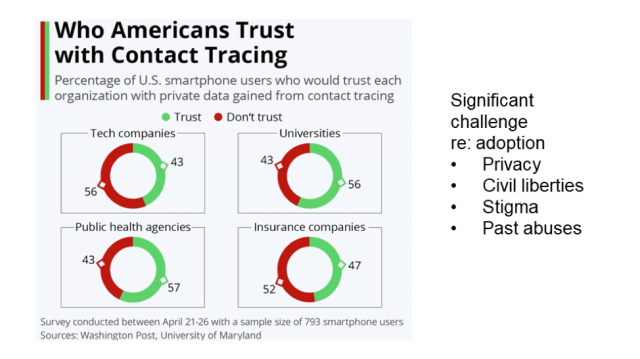

The success of digital apps in reducing the transmission and impact of COVID-19 will hinge on widespread, voluntary buy-in by the U.S. population, McClendon and Nielsen said. Given substantial mistrust of both government and large technology firms, developing solutions that safeguard privacy and civil liberties is paramount.

Lawrence, KS-based, non-profit CVKey Project was launched in May to pursue the goal of helping communities open responsibly without compromising personal privacy. McClendon is the founder of Google Earth and a former Google vice president; Nielsen is the former chief executive officer of the Washington, D.C.-based Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative.

Limitations of manual contact tracing

Traditional or manual contact tracing is designed to break the chain of exponential disease transmission by quickly working backward from known infected patients to identify and alert those with whom the individual has recently interacted. Public health workers then advise the exposed party to isolate or quarantine, depending on their condition and symptoms.

Significant barriers can undermine the efficacy of manual contact tracing, not the least of which are the labor-intensive nature of the process and the reluctance of many to accept calls from unknown numbers, Nielsen said. And if contact is established, a high level of trust must be established between the health worker and exposed individual to ensure appropriate action is taken.

Moreover, McClendon said, accelerating rates of infection in many states are making traditional contact tracing problematic. Florida, for example, has successfully traced the origins of 50% of their infected population. But with close to 9,000 new cases reported recently in one day alone, rapidly isolating the origins of each infection has become increasingly impractical.

Augmenting with digital tools

Digital solutions can serve as force multipliers that enable contact tracers to work faster and more effectively. Voluntarily downloaded apps identify whether, when and where a person has been in close proximity of an infected individual. A range of these solutions are emerging, McClendon said, though some are less effective than others. GPS-based technologies, for example, are both privacy invasive and not sufficiently accurate when it comes to identifying an individual’s location, particularly indoors, he said.

An alternative approach jointly developed by Google and Apple, known as Google/Apple Exposure Notification, mitigates the privacy and accuracy limitations of GPS-based apps by relying on Android and iPhone Bluetooth capabilities. The technology generates random number sets and then pairs with other phones that have the app installed.

The number sets are stored on the phone to assure privacy and if an individual tests positive for COVID-19, they’ll be asked to voluntarily upload their number sets to cloud storage run by a state or county agency. The process creates a mechanism for other apps to identify an exposure and notify the phone’s owner but also enables the original infected individual to remain anonymous.

The exposure notification will ask the user to alert a manual contact tracing team and a determination can be made whether isolation or quarantine is appropriate. Importantly, McClendon added, no data is shared with Google or Apple, and the random number strings prevent identification of infected and non-infected individuals by health authorities. Moreover, individuals’ whereabouts are never identifiable. Physical proximity to an infected individual is communicated to the user to inform their next steps.

Health verification apps

The CVKey project founded by McClendon and Nielsen is focused on the development of a related app that can help communities, companies and other organizations adjust economic, employment, educational and social activities based on up-to-date regional public health and community guidance. The CVKey opt-in app allows users to check their own health and potential exposure status through a series of questions to self-identify risk factors for spreading the virus.

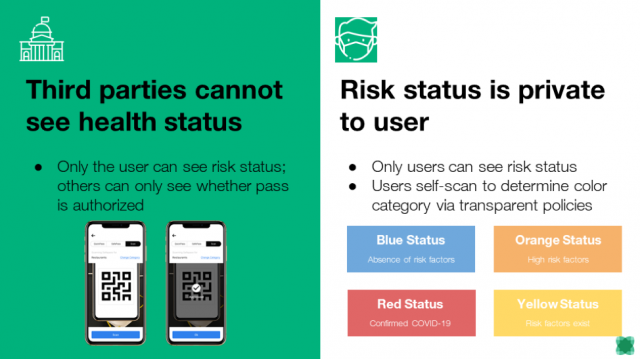

Depending on their answers, the user is assigned one of four color-coded conditions or states. These include Blue, for no known risk factors; Yellow, for when an exposure has occurred; Orange, for both exposure and symptoms; and Red, for users that have tested positive for the virus.

McClendon said the data is stored on the individual’s phone and never uploaded to any central database. The app does, however, download policies set by specific businesses and organizations to delineate rules of entry, which are then compared with the person’s health status. Based on these comparisons, a QR code is produced and the user informed if they may enter a specific building or not and what requirements might be in place, e.g. mandatory masks or off-limit areas.

A key objective of the tool, McClendon said, is to provide both individuals and organizations with data-driven, real-time safeguards to help eliminate potential exposures. Scanning an individual’s code at a restaurant and limiting access to those with a Blue condition, for example, would help ensure both safety and peace of mind for diners and staff.

The app’s additional ability to inform users of updated company or building-specific policies based on changing conditions could provide a “dimmer switch” that would help health authorities and employers reduce transmission risk without the need for a blanket lockdown.

The CVKey app is being piloted this fall at the University of Kansas, McClendon said. The QR coded displayed by the app will provide the university’s building monitors with a simple yes or no indication as to whether the individual’s health assessment meets the criteria to enter the building that day. Anyone generating a Yellow or Orange condition will be asked to communicate with the university’s health department.

“Our message to communities is that if you can help employers choose to adopt this app, there will be less chance of going into another lockdown,” McClendon said.