Consequences of COVID-19: Experts Forecast the Future of Health Care Costs and Utilization

The unprecedented collapse in patient volume sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic could reshape health care for years to come, but whether those changes ultimately prove beneficial or destructive remains to be seen, experts say.

What is clear is that significant risks and opportunities are beginning to emerge from the chaos surrounding the pandemic. Helping large employers understand and adapt to these developments was the primary goal of an expert panel discussion hosted May 6 by the Purchaser Business Group on Health.

Participants included Michael Chernew, director of the Healthcare Markets and Regulations Lab at Harvard Medical School; John Bertko, chief actuary and director of research for Covered California; and Jane Jensen, senior director of the health and benefits consulting practice with Willis Towers Watson.

Utilization off a Cliff

The extent to which demand for traditional health care services would be affected by COVID-19 wasn’t immediately clear as hospitals ramped up for worst-case scenarios and a surge in COVID-19 patients in early March. But with most elective surgeries cancelled and patients fearful of contracting the virus in any care setting, the utilization drop was immediate and severe for both hospitals and physician offices.

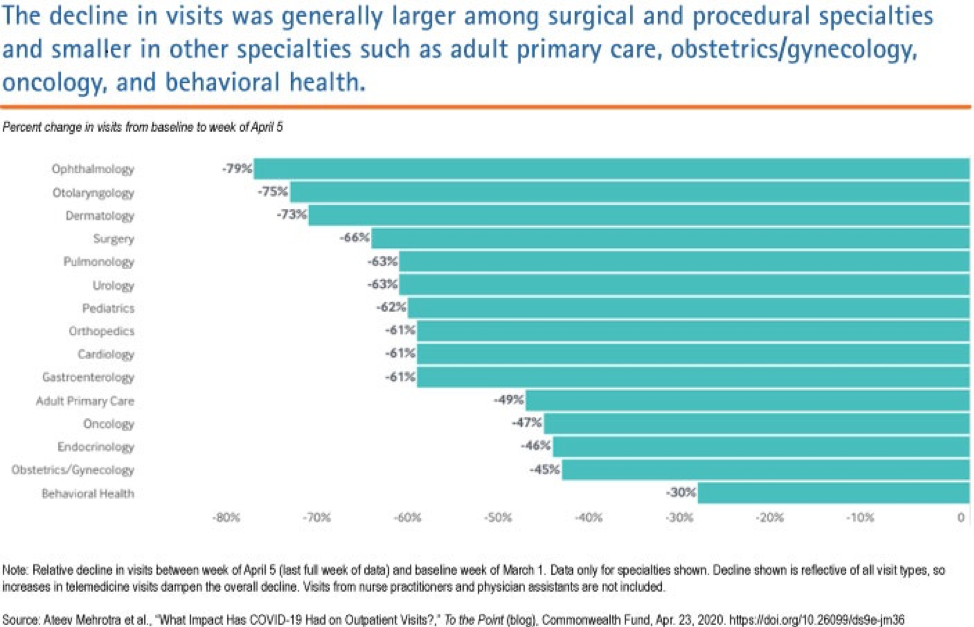

Chernew shared data provided by Phreesia, a health care technology company, and published by the Commonwealth Fund that showed the number of ambulatory practice visits nationwide (including telemedicine visits, fell by over 50% between March 1 and March 29. Office visits for some specialists dropped even more: Ophthalmology was down 79%; ear, nose and throat, 75%; dermatology, 73%; surgical office visits by 66%; and adult primary care by 49%. The most recent data from mid-April suggests only a slight recovery off the lows.

Hospitals have likely experienced similar drops in volume, with lost admissions far surpassing COVID-19 admissions and outpatient procedures down dramatically, Chernew said. At the same time, most are experiencing rising costs due to policy changes and equipment purchases necessary to combat the virus infection threat.

“By and large, hospitals are getting creamed right now financially,” he said.

Flipped Spending Projections: What It Means for Employers and Employees

The good news from an employer standpoint is that because of the volume collapse, pandemic-related health care cost increases projected as recently as six weeks ago now seem unlikely, and though there is a wide range of uncertainty, health care spending could actually fall by 5% in 2020 and remain flat or continue to drop in 2021, according to Chernew. That should translate to lower fees and health care spend for administrative services only (ASO) plans, with the savings accruing directly to employers, and by extension, their employees.

Jensen of Willis Towers Watson projected similar reductions in employer health care costs, a reversal from the estimated increases for 2020 made in mid-March that ranged from 1% to 7%, depending on COVID-19 infection rates and hospitalization rates. With infection numbers far lower than expected, Willis Towers Watson is now predicting spend reductions ranging from 1% to 4.5% for 2020. She said her organization anticipates COVID-19 workforce infection rates of about 1% for most employers, far lower than the 10-50% range initially predicted.

Given the backdrop of a federal deficit expected to exceed $4 trillion this year and the nation’s ongoing, Depression-level economic contraction, Chernew said pressure to control health care spending will continue.

“There’s going to be less money for everything,” he said. “Going forward, everyone is going to be looking to save money on health care.”

He predicted employers will likely reduce benefit generosity and narrow networks to accomplish cost reductions. But Jensen said many employers at this point are primarily focused on ensuring that coverage remains affordable for employees. Noting that many firms have already faced “gut-wrenching” decisions about layoffs, she believes most are more likely to look for savings through limits on provider choice as opposed to benefit reductions.

“I don’t think they don’t want to nickel-and-dime [those employees that remain] by changing benefits,” she said.

How Much Comes Back?

Bertko of Covered California and the other panelists agreed that vast uncertainty surrounds the ultimate disposition of care deferred during the pandemic.

“How much will we see rescheduled in the second half of 2020? How much will be deferred until 2021? And how much will just drift away and disappear?,” Bertko said. In his view, it will take considerable time before patients feel comfortable coming back into office settings.

Jensen’s organization analyzed the volume and types of care currently being deferred. The results ranged from high levels of deferral for office visits, dental care and non-urgent procedures to lower levels with acute emergency care and cancer care. The analysis further suggested that while some of this volume would be rescheduled, the majority would not, particularly when it came to office visits and urgent care.

Noted Chernew: “You can’t have a 50-60% drop and then expect that as soon as things open back up, everybody’s going to be doing 120% until they work their way through the backlog.”

All panelist agreed a potential second wave of pandemic infection was a wild card that could extend and exacerbate the demand decline.

Risks and Opportunities

Should the volume reduction prove protracted, the implications for all providers are grim. Hardest hit will likely be already underfunded and vulnerable primary care practices. Bertko said primary care groups in California are seeing as much as a 70-80% decrease in office visits.

A survey of primary care providers in late March revealed that nearly 80% of clinicians reported their practice was facing severe or close-to-severe financial strain, and 20% said their group might need to close temporarily. If the financial pressure continues, some practices could close permanently or be acquired by large health systems, insurance companies or even venture capital firms.

Panelists said the consolidation of primary care practices could reduce carriers’ ability to negotiate better prices on behalf of employers, disrupt existing provider networks and limit progress toward pay-for-performance reimbursement models.

“We at Covered California do not want primary care practices bought up by several very large hospital systems,” Bertko said.

For employers, the current landscape presents substantial opportunities to focus on benefit designs that more effectively steer employees to high-performance providers and accelerate the transition to value-based reimbursement, Jensen said.

“Not all hospitals are created equal,” she said. “So payment reform and steerage go hand-in-hand. But at the same time, we really need to be mindful of total cost of care and not just focus on price.

“We also have to recognize that providers need to stay in business. Ultimately, we need to find ways to pay the right amount, fairly, to the right folks, and not cut off our nose to spite our face.”

The panelists agreed that determining whether the patient volume decline is temporary or marks a sea-change in how health care services are consumed represents the most important unanswered economic question surrounding recent events.

“We are in the midst of a natural experiment,” Bertko said.

Added Jensen: “What’s happening now may or may not change patterns longer term; people may or may not think differently about how they use healthcare in the future.”

While a permanent reduction in overutilized, low-value care would be a major positive for the system as a whole, finding ways to prevent it from coming back as providers scramble to recover lost revenue will likely prove “a huge challenge,” Chernew said.